Why we aren’t ‘all in this together’

Our Empowerment Programme Officer Ben Pearson shares some reflections on class and COVID-19.

I spoke to a young person in Darwen, Lancashire last week whose only way of getting online during lockdown was via their mobile phone. According to the Office for National Statistics, 12% of 12-17-year-olds don’t have access to the internet by a computer or tablet at home, and in areas of deprivation its likely this is much higher. It’s ironic that only a few months back people laughed at Jeremey Corbyn’s ‘radical’ promise to give all households free broadband. This comes at a time when we are more reliant on digital technology than ever before, whether that’s for staying connected to family and friends, home-schooling or ordering groceries.

It’s all very well telling people not to leave their homes, far easier for those though with houses big enough to give people space and a garden.

Working-class communities are being hardest hit by COVID-19, and many of those implementing measures to deal with the crisis fail to understand the grassroots reality. Take lockdown measures for a start: it’s all very well telling people not to leave their homes, far easier for those though with houses big enough to give people space and a garden. If you’re in a tower block or terrace with little or no outside space this becomes much harder. We see and hear stories of those more privileged filling their days with novel pastimes, baking, reading, exercising to Joe Wicks, knitting, learning a new instrument, and going on long country walks. The reality is many never had the disposable income, access, space or indeed the calm concentration to engage with any of these prior to lockdown, and with heightened levels of anxiety & stress, now is hardly the right time to start.

Home-schooling unfairly disadvantages those in working-class communities due to digital exclusion, lack of space and resources, and frankly more pressing issues to be worrying about, like putting food on the table.

Times are evidently difficult for all, we’ve never experienced a crisis like this in our lifetimes, and we are all learning to adjust to new ways of living, working and coping. For those with children, home-schooling is no longer an activity for the privileged liberal left with time on their hands; instead it’s become a necessity. Much like lockdown, it unfairly disadvantages those in working class communities, who face digital exclusion, lack of space and resources, and frankly more pressing issues to be worrying about, like putting food on the table. Another young person in Lancashire said how they hadn’t been able to get online to access lessons since school had closed for lockdown, creating unnecessary disadvantage. And the amount of time some schools expect young people to continue to engage in education is unrealistic and unfair; one’s health and wellbeing should be a priority. With an education system that runs like a business, with more interest in grades, it’s hardly surprising this is happening.

Buying the simplest of ingredients to bake with would be a luxury, especially for those with children eligible for free school meals, families I’ve spoken to receiving as little as £11.75 per child, per week.

Whilst baking sourdough for the first time might be an exciting activity for the privileged middle classes, far more are struggling to put meals on the table. When Boris tweeted ‘Stay Home, do some baking’ he clearly failed to understand the reality of so many, the patronising tone cringe-worthy. Buying the simplest of ingredients to bake with would be a luxury, especially for those with children eligible for free school meals, families I’ve spoken to receiving as little as £11.75 per child, per week. This allowance is emailed out as a voucher by individual schools to be used in supermarkets, either online or in store. This provides challenges for many: not having internet at home, not having a printer to print the vouchers, not being able to afford the minimum spend if ordering online, not being able to get a delivery for days or weeks, or being unable to get to one of the supermarkets the vouchers can be spent at. It’s worth noting the official government website lists M&S and Waitrose as two of these supermarkets – clearly places lots of families in receipt of free school meals regularly shop at. For others a ‘grab bag’ is provided by the school. One school in Lancashire, but possibly many more, requires students to attend in uniform to collect these. Talk about those in positions of power making rules that stigmatise the most disadvantaged – how about a sign spelling out ‘I am poor’? Chances are many of these kids won’t attend due to fear of embarrassment, therefore going hungry. Why can’t we just ensure families have enough money in their pockets in the first place, and empower them to make their own decisions on how to feed their families?

When payday came, many were already living from one paycheque to the next; having anything spare to stock up on essential items wasn’t a reality.

The rations that many shops have put on certain food items have hit working-class communities too. Whilst the middle classes panic bought, filling car boots with an endless supply of toilet paper and rice, stockpiling ‘emergency freezers’, others were waiting for payday. When payday came, many were already living from one paycheque to the next; having anything spare to stock up on essential items wasn’t a reality. Those living in working-class communities are less likely to own a car, making it difficult to do a ‘big shop’. Larger supermarkets are often not close by, and so it requires many trips to do smaller shops, often paying a premium at more expensive local stores. For larger families the one-item restriction isn’t realistic; one mum told me how a bag of chicken wouldn’t fill the plates of everyone for one mealtime. And so, whether those in working-class communities want to or not, the likelihood is they have no choice but to leave their home more often to feed their family from one day to the next, putting themselves at more risk.

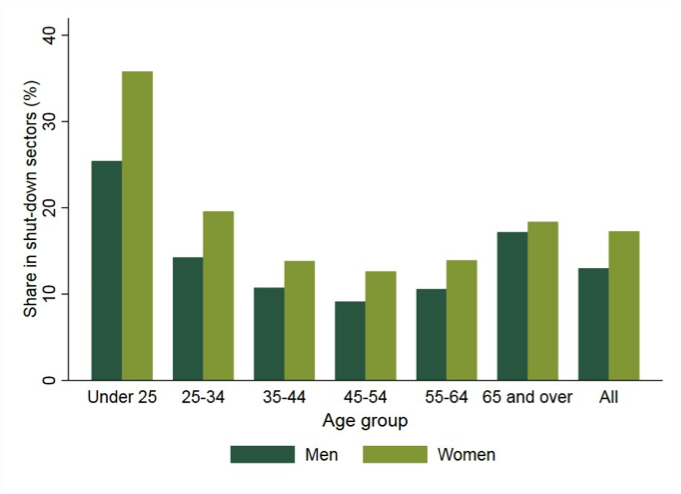

Those able to work from home are more likely to have jobs that pay more; manual workers in lower-paid work have no option but to leave home, be that cleaners, bus drivers, NHS staff or those working in retail.

The government did listen to people who said Universal Credit wasn’t enough to live on. It’s just a shame it wasn’t to those communities who’ve said this since its introduction. Of course not – it was now that ‘hard-working’ people with more middle-class jobs might actually need welfare support. People with more power like themselves, whose voices they were prepared to listen to. And so from 6 April, the weekly allowance went up by £20 per week. Then there are the workers. Those able to work from home are more likely to have jobs that pay more; manual workers in lower-paid work have no option but to leave home, be that cleaners, bus drivers, NHS staff or those working in retail.

Weakened safeguards and lower care standards will impact those already at risk, such as disabled people and those with mental health issues.

Those in working-class communities & from marginalised groups are also more likely to be victims of newly introduced police powers. The police are now able to arrest anyone ‘who is or may be infectious’ and take them to a ‘suitable place for assessment’, and this is likely to impact communities that are already over-policed. Weakened safeguards and lower care standards will impact those already at risk, such as disabled people and those with mental health issues. Powers to restrict events and gatherings may silence those who want to speak out in protest, and with these new powers being introduced at such a pace, it’s difficult for people to understand how to comply or challenge them. It’s far easier to rush things through in a crisis when people are distracted on the immediate issues, but these state powers risk drastically reshaping our civil liberties for years to come.

This is ironic, and further shows the class divide when we hear of privileged individuals breaking or bending the ‘rules’ – with the prime minister’s father Stanley Johnson saying early on he would ignore government advice and go to the pub if needed, and more recently Scotland’s Chief Medical Officer (who has since resigned) traveling to her second home twice during lockdown.

Providing emergency food parcels or vouchers to school children isn’t the answer, families should have enough money in their pockets to respond without the need for charity.

Finally, the idea that we are all ‘in this together’ is difficult to comprehend. We are made to believe that people coming out of retirement and vast numbers volunteering is something to be celebrated. Instead we should be angry that austerity measures that have drastically underfunded the NHS and other vital services have left us in this position. Providing emergency food parcels or vouchers to schoolchildren isn’t the answer, families should have enough money in their pockets to respond without the need for charity. If everyone had an adequate income, charities could better respond to those deep in crisis, rather than filling the vast gaps in provision that should be provided by the state. This isn’t only a public health crisis but a social crisis, one that shines a light on the deeply entrenched inequality in our society, not only nationally but on a global level.

It’s easy for many to think this isn’t a time for politics as they try to stay positive during the most challenging of times. Communities have come together across the country to support their friends & neighbours; tremendous generosity has been shown, and its important for us all to stay hopeful and resilient. It is, though, a time that we should challenge, scrutinise and speak out more than ever before, an opportunity to come together in solidarity and change things for the better, for generations to come.

Stef Benstead’s book Second Class Citizens: The treatment of disabled people in austerity Britain is available from the

Stef Benstead’s book Second Class Citizens: The treatment of disabled people in austerity Britain is available from the