This is a guest series of stories that challenge and change. These are intentionally contrary stories that push back against negative ideas, and force us all to re-examine negative stigmas and stereotypes. They are longer than our usual blogs, and we encourage you to read them when you have the time to do so in full.

These stories are told by Stef Benstead, a social justice campaigner, Manchester Poverty Truth Commissioner, and an expert on the mistreatment of disabled people.

These stories are told by Stef Benstead, a social justice campaigner, Manchester Poverty Truth Commissioner, and an expert on the mistreatment of disabled people.

Meet Emma...

Emma is your ‘typical’ workless benefit claimant: overweight; in a power chair; all-but never worked.

She’s the kind of person who’s pointed out on the street as an exemplifier of all that’s wrong with Britain. The obesity epidemic; the eating of fast-food and processed food and sweets and ice creams; the lack of work ethic; the attitude that believes it’s right and better to take state money than to work.

The person who had children whilst on benefits, rather than wait to be able to afford them. The person who uses abortion as a birth control method. The person who fights like a tiger for her ‘entitlements’, but can’t keep a stable relationship.

Except that that’s not Emma’s story… That’s the narrative that rich and lazy people weave in their heads around people like Emma, because it’s easier than finding out the truth.

Do not jump to conclusions

Finding out the truth would mean going to actually speak to people like Emma.

It would mean refusing to make any assumptions about the reality behind the image, and refusing to pass on one’s imaginings as the ‘truth’ about so-and-so in a piece of faux-shocked gossip.

Sometimes I wonder if the reason middle- and upper-class people jump so easily to false conclusions about poor and struggling people is because they’re reflecting their own selfishness and greed onto a people who are actually less selfish and more community-minded than them.

Why do so many judge falsely?

But that would be to ‘other’ the rich, and would be unfair.

Whilst there is data showing that richer people are more selfish and greedy, it isn’t right to assume that every rich person is inherently morally inferior and to be judged negatively.

Many may simply be ignorant, living as they do lives that are so divorced from the bottom half of the UK income or class scale. They simply don’t know what is going on in these other people’s lives, and for whatever reason many of them choose to judge these people falsely and negatively.

Seek the right narratives over the easy ones

It is easy to judge Emma from the outside. But judging her and writing her down as a skiver and feckless mother doesn’t make that pejorative narrative true.

It’s the easy narrative, because it lets the richer person off the hook for showing justice and generosity, and even allows us to kid ourselves that justice and generosity is to let this person suffer for their sins until they learn to do right. That’s exactly how God treats us, of course, and is why God had no problem when a person in great debt shows no mercy to someone in a little debt.

Meet the real Emma...

So let me introduce you to Emma. In her mid-thirties, she’s training in lay ministry as a youth worker as part of her training to become a vicar.

Where many middle-class vicars have only their brain to draw on, Emma has personal experience and extensive knowledge of what life is really like for many people. That invaluable insight is beginning to be recognised by the Church of England and other denominations.

She has two daughters, one a young adult and one in primary school. She has a sharp mind and a strong drive to be engaged and active. In periods where she has been unable to obtain work, she has engaged in lots of volunteering and various training and skills courses. These courses range from basic CV-writing, to life-skills, to crafts. Whatever was available at the time.

She has a back injury from an abusive husband who kicked her down the stairs. When the doctor told her she’d be in a wheelchair within a year, she didn’t want to believe the doctor about the ongoing deterioration of her spine.

But the doctor was right, and Emma now depends on her powerchair for more than occasional and short-distance mobility. She struggles with anorexia, and her body fights back by shifting to starvation mode and clinging on to calories.

Emma: recovering from abuse

She has ADHD, autism and dyslexia. When she entered secondary school, she was functionally illiterate and yet still undiagnosed. Like many people with ADHD, Emma’s body is poor at telling her that it’s time for food, and this failure to eat regularly compounds the anorexia in her body’s insistence on its need to store rather than spend the calories it gets.

Emma had a difficult childhood. Her dad wasn’t around, but her mum worked as a cleaner and her step-dad worked in a paint factory. Both were binge alcoholics, leaving the children in the care of a babysitter whilst they socialised. That, of course, is an entirely normal and middle-class proceeding, and shouldn’t attract any censure. The problem was with the abusive parenting, which caused Emma to leave home at 17.

Emma: poorly supported in school

Emma struggled at school, both because of bullying and because her dyslexia meant she couldn’t keep up with lessons. She enjoyed maths, but other lessons were challenging. It wasn’t until secondary school that anyone paid enough attention or care to get her assessed and diagnosed, and she was then given an amanuensis to help her in her work. In this way, she was able to pass GCSEs in maths, science and English.

After school, Emma signed up to train as a mechanic. Unfortunately, she had undiagnosed epilepsy, and was experiencing absence seizures. To the garage, the petit mals, coupled with her poor social skills and limited literacy, made her look like a slacker and scrounger. They fired her within a year.

Facing homelessness

Emma was still being abused at home by her mum. When she lost her mechanics position, she left her mother’s house. She stayed for a week with her sister, but her sister was also abusive. Emma was able instead to get a place at a hostel, a few miles away from where she had been brought up.

For middle-class people used to the luxury of cars, this may sound like living in one’s home area. For people with limited means to travel, being separated from your community like that is a big deal.

Emma joined what was a youth training programme, giving her support in CV-writing; confidence building; budgeting; household management; and travel. This was helpful for her, with her learning difficulties and relatively limited education. But it wasn’t on-the-job training. Whilst she was on the programme, she also worked part-time as a cleaner, to top-up the financial support she received as part of the programme.

Facing rejection and unhappiness

Emma is a bright woman. But her learning difficulties hid this from the casual observer, and blocked her from getting any meaningful job training. The constant rejections were demoralising and dispiriting. The worst was when she was rejected for vicar training, on the grounds that she would not be able to handle the work. She felt that God had given up on her as well as the rest of the world.

She wasn’t receiving anything to help her maximise her career, fulfilment or earnings potential.

Nor was she receiving anything to help her process the abuse she had grown up with.

Consequently, she was both bored and desperately unhappy. She entered a time of self-destruction, wanting to die and managing the despair with dating, drink, and drugs.

Illness, pregnancy and false accusations

Emma was taking contraception, but she didn’t know that epilepsy medication interferes with the efficacy of contraceptives. She became pregnant. The pregnancy drew her to the attention of social services. She was found a place in a mother-and-baby home, where she was able to live for two years. When her baby reached six months, she was eligible for a place on social services nursery.

This allowed Emma to engage in training and volunteering. But baby caught impetigo from nursery – and Emma was falsely accused of neglect and of burning her child, because impetigo can look like burns.

Emma stopped her drinking and drugs when she became pregnant, and has stayed away ever since. But her learning difficulties and epilepsy made her an unfavourable mother in social services’ eyes.

This was a time when people with learning disabilities were still being sterilised, and Emma’s own sister had undergone a court-ordered sterilisation. Emma had also struggled with physical illness during her pregnancy.

When contraception failed again and Emma became pregnant for a second time, with her baby only three months’ old, social services told her she could have either the current baby or the pregnancy, but not both. If Emma continued with the pregnancy, they would take her three-month-old away, and they would likely also take the new baby when it was born.

Emma asked if she could carry the new baby to term and then have it adopted, but was told no. If she went with that plan – or any plan that involved continuing the pregnancy – her three-month-old would be removed.

This command may in part have reflected Emma’s physical health difficulties with her first and her now second pregnancy. But it is telling that she was never offered support to keep her pregnancy, and her three-month-old, even to give the new baby up for adoption. Emma was compelled to have an abortion.

Navigating the benefits labyrinth

Emma didn’t know what benefits she was entitled to, so only claimed disability benefits for her epilepsy, income support as a young mother, and child benefit. She didn’t know she should also have been getting child tax credit. When the DWP finally realised that Emma’s claim for child benefit was also in effect a claim for child tax credit, they paid her over £4000 for a year’s backpay. It is not at all clear that the DWP would be so fair today.

At the same time, Emma was no scrounger. She was no mythical ‘teenage mum’, having a baby in order to avoid work. Raising a young child is hard work and also often boring, monotonous and isolating. Emma had had no intention of being a mother at 19; she wanted to work and train and improve herself. She wanted a career and a life and money to live off. Still, having a child helped to save Emma’s life.

Finding home, purpose and training

Boring as it often was, it helped her to live with her memories of her own abusive childhood and the long-term impacts on her own wellbeing and relationships.

After two years, Emma was offered a social house. Whilst her child was still young, she went on a number of training classes. Mostly these were still low- or non-competitive skills, like cooking or photography, which might stave off her boredom but didn’t help with getting a job.

Eventually, though, she was offered a place to train as a peer educator in sexual health and wellbeing. For several years, this was her work. And then the Conservatives came back into power, in coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

Over a period of years, with much striving, and with some help from church (the mother-and-baby unit) and state (social housing, nursery place from six months, access to training, and a meagre but better-than-nothing income), Emma had started to build herself a life.

She had a stable job that she enjoyed and was good at, and therefore had a future. And then the Government – in the name of Big Society and helping people to get out of poverty and into work – pulled it all away from her. They cut funding to the programme in which Emma worked, and her job was removed.

Lifelines ripped away

Emma’s job had previously been used as a reason to take her disability benefits away from her.

Now she had neither benefits nor a job. Yet she’d still had epilepsy, dyslexia, ADHD and complex PTSD the whole time.

She had to start again. Back on benefits; back to struggling; back to insufficient money through no fault of her own. Eventually, she became one of many who had to turn to foodbanks to survive.

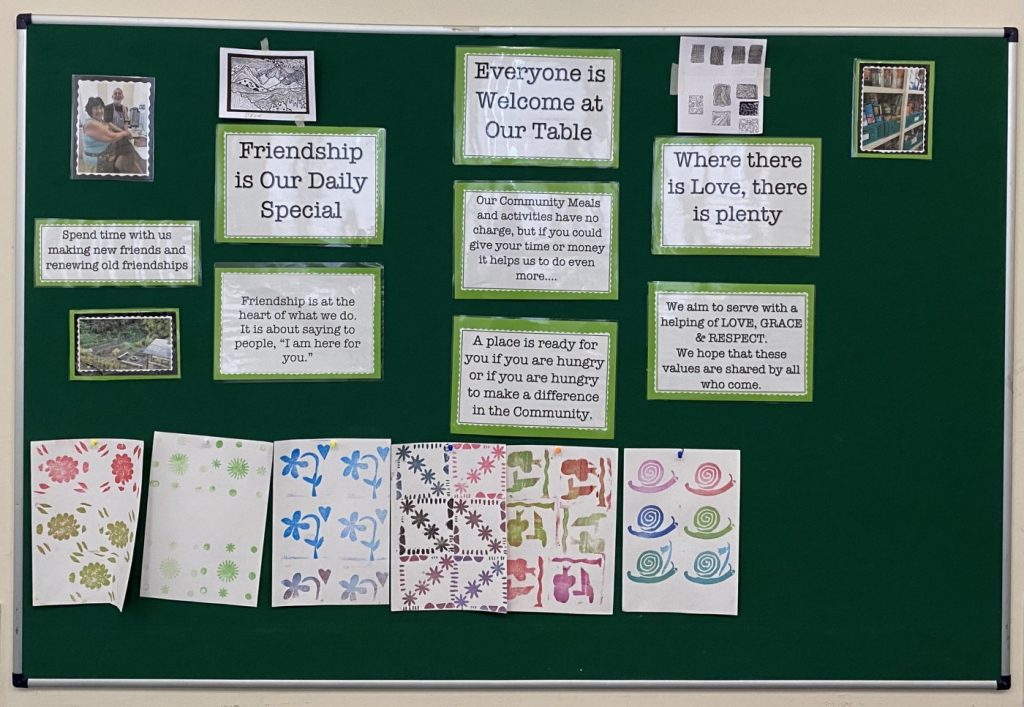

The foodbank was run by a local church. Going to the foodbank encouraged Emma to start going to church again, after turning away from faith as a young adult. The church has supported her since that time, and it is because of that that she is now training to be a vicar.

Like with everyone, what helps Emma’s life is not punishment but support. Support for housing, income, childcare and training is what got her her job. The housing, income and childcare support were all vital to give Emma the space to engage in training that led to her job. Later, it was the support of foodbanks that helped Emma find community that eventually led to her training to be a vicar.

What you didn't see at first: the care, the compassion, the sharp mind and more

Conversely, the withdrawal of support is harmful. The cuts made by the Conservative Governments after 2010 caused Emma to lose her job. Her health problems meant it was extremely difficult for her to obtain new work, and it has taken years from when she first left the peer educator role before starting vicar training. Those years could have been more fruitful if cuts had not been made.

From the outside, Emma may look like the epitome of the sickness claimant who is ‘only’ there because of obesity. But that’s because all you can see from the outside is the obesity. You can’t see the spinal damage, the complex PTSD, the dyslexia or the ADHD. Equally, you can’t see the sharp mind or the depth and breadth of experience and knowledge that Emma has. You can’t see her compassion, her care, and her sense of fun. You can’t see the real person and her inherent value.

What you can know, however, is that you should never judge by the outside.