A guest blog on the cost of living crisis by Dr Naomi Maynard of Feeding Liverpool and Natalie Davies.

April Fool’s Day, our kids were late back from their school trip. A blessing really, giving me time to stop and listen. Natalie’s been a good friend for over three years, since we were pregnant at the same time with our littlest children and I was new to Everton. Where we live doesn’t have the best statistics, we have the highest Index of Multiple Deprivation score for the city, are one of England’s top ten most economically deprived food deserts, and have significantly more than the national average of children, by reception age, who are obese. New research has also identified our constituency as the least able to withstand the rising cost of living in the UK. But for us it is home, an area with amazing community, a beautiful view of the city and teachers who champion our kids.

The cost of living with the Poverty Premium

“Over six months of trying and still nothing,” Natalie exclaims. She has been trying to switch from her pre-payment energy meter to a direct debit energy deal, but none of the major suppliers will have her. “It’s exhausting, they just say ‘we have no-one in your area to do this’ or ‘phone again in a few months’, I want a smart meter and to be on a direct debit. I know this will save me money but what can I do?

“I couldn’t even take up Martin Lewis’ advice to top up our meter as much as we could before the price changes came in at the start of April. I didn’t have anything spare that week to put on, and even if I did my supplier said they’d recoup their losses next time I topped up! What a joke!”

In charity and academic speak, what Natalie is experiencing is called the Poverty Premium – when lower-income households are paying more for essential goods or services because the best deals aren’t available to them. This means the impact of price rises aren’t experienced evenly across all pay brackets, unfairly putting significant, avoidable additional pressure on lower-income households trying to keep their heads above water.

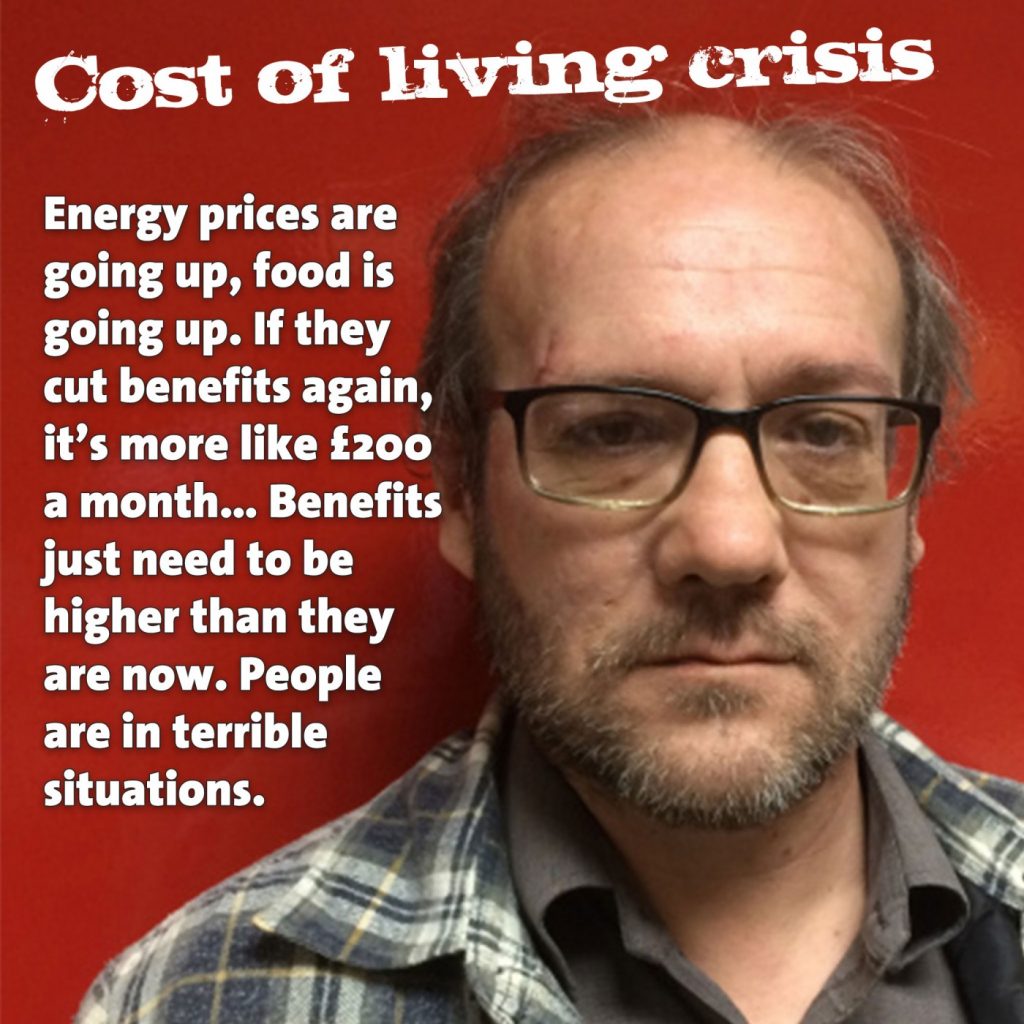

Natalie works part-time for the NHS as a cleaner, bringing home just £9.20 a hour. This, coupled with her Universal Credit entitlement, goes quickly once she has paid for rent, council tax, energy, transport to work, food and clothes for her two children. She also is working towards a degree part-time. For Natalie the end of the £20 per week Universal Credit uplift in October signalled the end of ‘Funky Fruit Fridays’ where she’d take the kids to the supermarket after school to pick fresh fruits to try over the weekend. She’s worried about the energy prices going up and what it’ll mean she has to cut back on. Her household budget, like those of so many others, simply doesn’t have many more places it can be cut.

Real solutions to the soaring cost of living

As we chat, my grand phrases about how we can ‘redesign this man-made economy’ and need to ‘ensure those in power know the reality on the ground’ suddenly feel hollow: change just isn’t coming fast enough. Yes, the Chancellor announced additional funds for our council to distribute through the Household Support Fund, and we have the excellent Liverpool Citizens Support Scheme and many charities around who will support households during this crisis. But will this be enough? Is this really the solution? Our lower-income households need better wages, a stronger safety net and fair access to the very best deals.

The school bus pulled in, and we were onto the next thing: playtime, dinner, bed. As we parted Natalie threw out the challenge “So, when do we riot?” Frustration, hopelessness, injustice, outrage spilling out in five short words, spoken with smile.

Be part of a movement that’s reclaiming dignity, agency and power