What I found when I visited one of Birmingham’s Local Pantries

James Henderson, the Development Coordinator for the Your Local Pantry network, celebrated our 40th anniversary at a Pantry on 6 July.

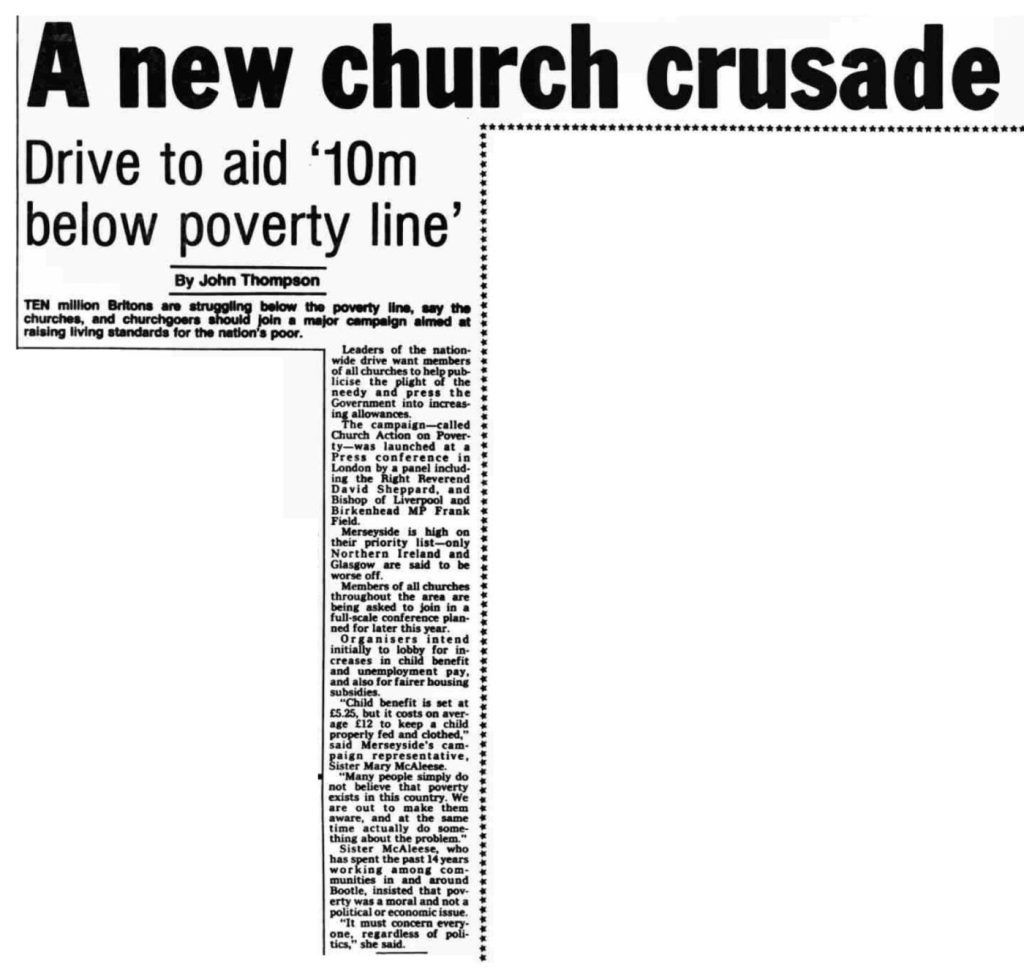

Birmingham Yardley Wood Pantry was set up in November 2019 but this was my first visit. The Pantry is located in Yardley Wood Baptist Church and was set up in partnership with Your Local Pantry – a key strand of Church Action on Poverty’s work to uphold dignity, agency and power for all.

As with all of the Pantries that I have visited so far, I was really impressed with the kindness of the volunteers, their dedication to the members and the fun and banter that was happening throughout the session.

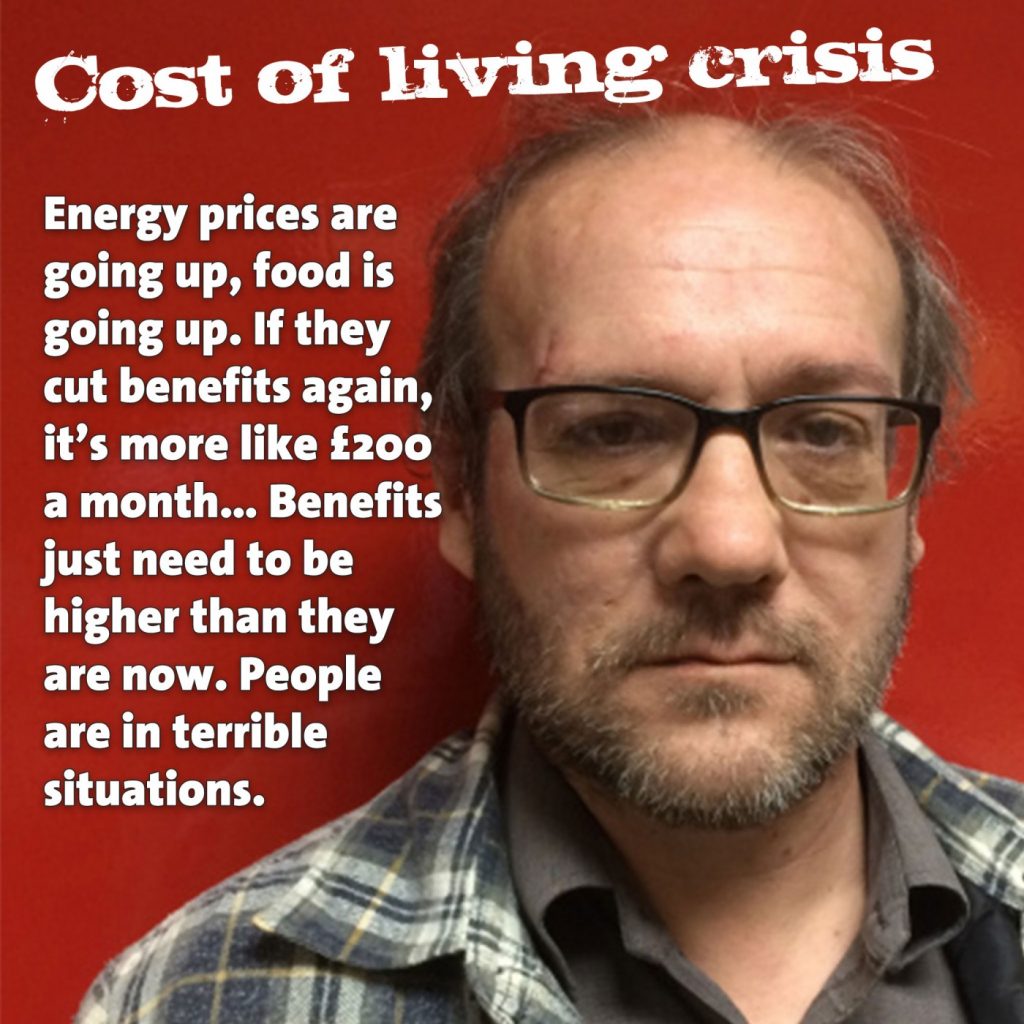

Each member was greeted with a warm smile and offered a drink and some cake. Members gathered around neat tables to chat to each other and to the volunteers, offering mutual support and a listening ear to each other. There was even a member of staff from a local advice agency, making it really easy for members to ask about help with rising energy costs and some issues they were having with their benefits. Children quietly played in the corner with some toys and a volunteer, as their parents browsed the shelves in peace.

The shelves of the Pantry were well stocked, with volunteers on hand to chat to members as they shopped. This level of choice was very important to members, helping them save money and help to prevent food waste.

Being part of a network really helps with sharing wisdom and expertise. As well as the local partnerships that Yardley Wood Pantry have built and invested in, their membership of the Your Local Pantry network means that they can share learning with another 70+ pantries across the UK and participate in joint training. This is especially important, as access to food supply gets more difficult and costs rise.

My visit ended on a sugar high, as I got to sample the brilliant and tasty chocolate cake baked by Donna, one of the pantry volunteers. A huge thanks to all the members and volunteers who helped us celebrate!

Be part of a movement that’s reclaiming dignity, agency and power

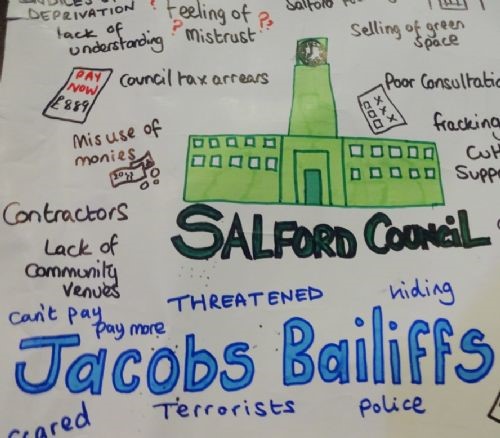

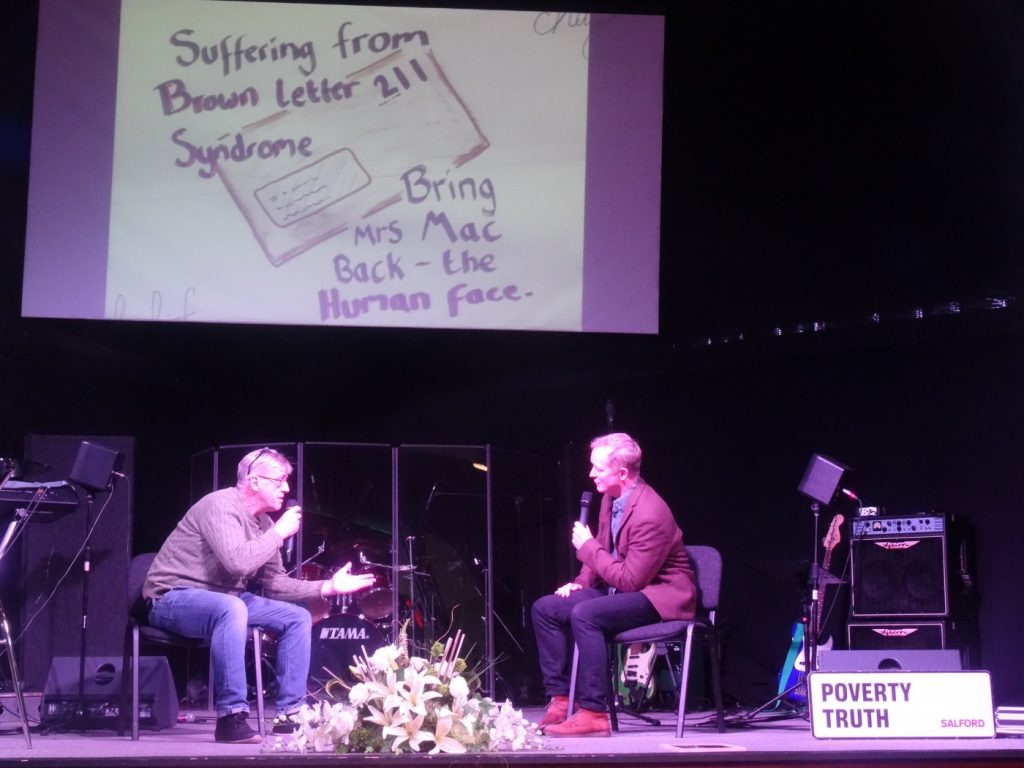

Niall Cooper, director of Church Action on Poverty, asks: How do we build dignity, agency and power together as a society?

Niall Cooper, director of Church Action on Poverty, asks: How do we build dignity, agency and power together as a society?